Tony Hawk and Kevin Staab Interview

Tony Hawk and Kevin Staab at the Tracker Barn.

Tony Hawk and Kevin Staab Interview

By Larry Balma and GSD

Simply put, Tony Hawk is the greatest, most famous, and successful skateboarder of all time. Back in the 1980s, his ability to execute original groundbreaking technical tricks on command led to a vert contest dominance that is unmatched to this day. In fact, the list of advanced tricks he invented, including the 720 and 900, can and does fill up pages. Tony has appeared on countless TV shows, movies, magazines, and products, including the popular Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater series of video games. Today, when Tony’s not skating or being blitzed by the media, he runs the Tony Hawk Foundation, which helps fund public skateparks in low-income areas.

Originally from Phoenix, Arizona, Kevin Staab has been a So Cal local since the very late ’70s, when he logged in plenty of time at spots like Del Mar and Tony Hawk’s ramp, inventing tricks like the blunt and the fakie Ollie. Well-known for his pirate-themed decks on Sims, Kevin also headed up a short-lived apparel brand called 90. Still to this day, if you dare to stand up on the coping block of a tall vert ramp or pool, Kevin won’t hesitate to float an Ollie over your face.

—GSD

Staab in the early days at Del Mar Skate Ranch.

LMB: When did you guys get your first set of Tracker Trucks?

KS: Right after the Del Mar park team sponsored me, Lance Smith picked me up and put me on Tracker. So, it was that quick. I remember the day very well at Del Mar.

TH: I think I asked Lance for a pair of trucks at a Reseda ASPO contest in 1979-’80. I was supposed to be sponsored by Indy, but they never gave me anything. I asked for new trucks, and they sent me a baseplate. So, I really just wanted a new set of trucks and I knew Kevin was riding Tracker, then Lance offered me a set, so I kind of put myself on Tracker.

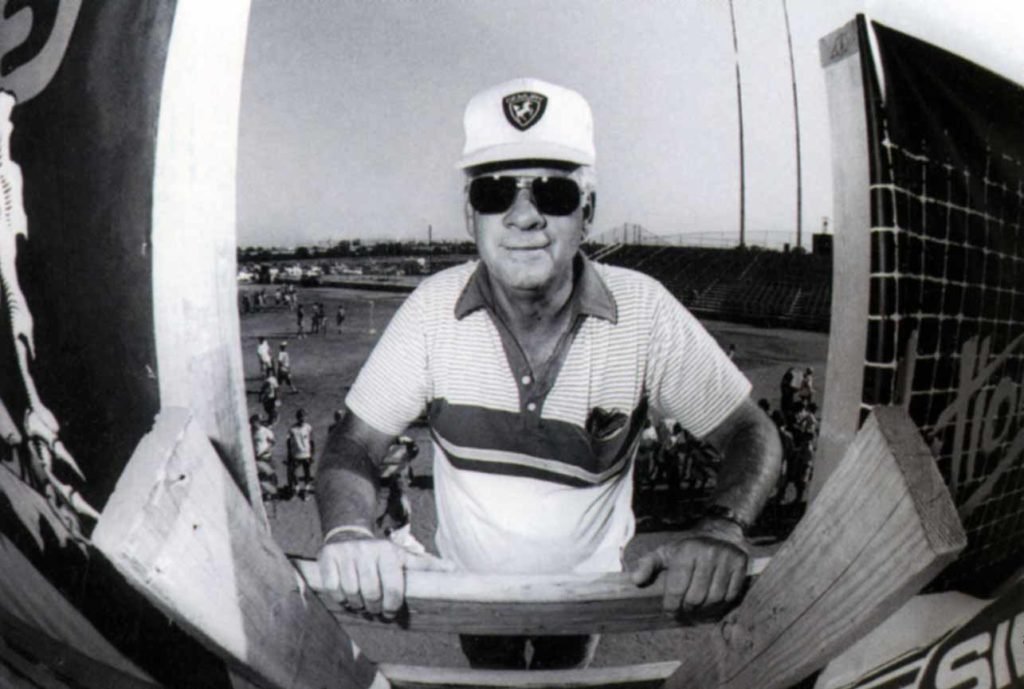

Tony’s Dad, head of the NSA Frank Hawk. Photo: Grant Brittian

LMB: Tony, you and your dad came down to Tracker at our new building in Carlsbad one time, and he wanted our opinion on which deck brand you should ride. I think you were riding an Alva deck at the time, and the question was, “Who is this Stacy Peralta guy?”

TH: Oh, I was riding for Dogtown, but they went out of business without telling any of their riders, me specifically. I literally found out from Stacy. He called me and said, “Hey, man, I heard that Dogtown went out of business.” At the same time, G&S was asking me about riding for them, and I just wasn’t sure what I wanted to do. I was leaning more toward G&S because they were San Diego-based, then my Dad wanted to gauge it, too, and I think he asked your advice because you were the industry expert.

LMB: He didn’t know Stacy, and wanted to know what kind of guy he was.

TH: I didn’t know what a monumental decision it would be for me. I definitely knew that the Bones Brigade was the most elite team at the time. As much as I liked G&S and their riders, I thought if Stacy’s really interested in what I do, then I should ride for the Bones Brigade because that’s the team.

Hawk invert at Del Mar Skate Ranch while Stacy Peralta and Craig Stecyk film. Photo: Grant Brittian

LMB: Kevin, do you remember when we hopped the fence at Colton skatepark and almost got arrested?

KS: Yes, I do, because those photos have resurfaced a couple of times. I was really afraid being there. I don’t know who was more afraid—me or Adrian Demain—because I remember riding the pool for a little bit and riding the medium snake, then the cops came when we got down to the bottom. I was like, “Oh, great. I’m going to get in a lot of trouble for this.” You guys kind of played it off, making like it was going to be way worse for us by talking to the cops. “Okay, let’s just scare these guys. It’s okay, we’re going to let you go.” Yes, that scared me. Thanks for that (everyone laughs).

LMB: How did it feel to ride skateparks after they were closed down?

KS: It was the best feeling ever. One of my favorite times was when Tony invited me back to Del Mar because they were filming Thrashin’. He was like, “Yeah, dude, we can ride the pool.” I was super excited. I walked into the pro shop, and all of a sudden, it was like, “Cut! Hold on, who’s that guy? What are you doing in here?” I said, “I’m going out back to skate the pool.” They asked, “Are you in the movie?” I said, “Yeah.” I had no idea, you just said come ride, so it was great. I went out and got to ride for the day, we got to ride the next day, and at the end of the second day, I got a check.

TH: Del Mar was closed at the time, and because the production company had their own insurance, they could open it up and let us skate. So, we got to skate Del Mar one last time and got paid for it.

Hawk soaring on the Animal Chin ramp in Oceanside. Photo: Grant Brittian

KS: I was so excited I got to fly back from Arizona and go there. It was insane.

TH: I never got to skate Carlsbad. My dad drove us there and talked to the security guy with the rock salt shotgun. My dad tried to talk him into letting us skate, but the guy wasn’t having it.

KS: That guy was scary. I remember that.

TH: Yeah, that was my one regret. I didn’t get to skate there. I didn’t get to skate Spring Valley, either, because I wasn’t old enough for a membership.

KS: Breaking into High Roller was another good one because that was my home park in Arizona, and it was one of the last ones left. I remember Todd Joseph and I got to go ride one day. We tried to hop the fence and got pretty far until the cops came. We were lucky that Todd’s mom came to pick us up because she was really cool about it. She was like, “You don’t need to punish the boys like this. They’re good kids, they just want to skate.” She actually talked them out of giving us community service, which is pretty awesome. I was actually more scared riding there because it was Arizona, and it’s scary going to jail in that place. But, we got away with it. Then there was the other fun thing about getting busted by the cops and using other people’s names. I was Mike Smith one time when I got busted street skating. That was fun.

LMB: That’s classic.

KS: It was more of an adventure back then in the ’80s. It was awesome to be able to go do that stuff, like jump over the fence ride the pool. You had 10 to 15 minutes before the neighbors or the cops came. Yeah, that was really exciting. Then you had your parents telling you that’s a bad thing to do. Sorry, mom, I never changed.

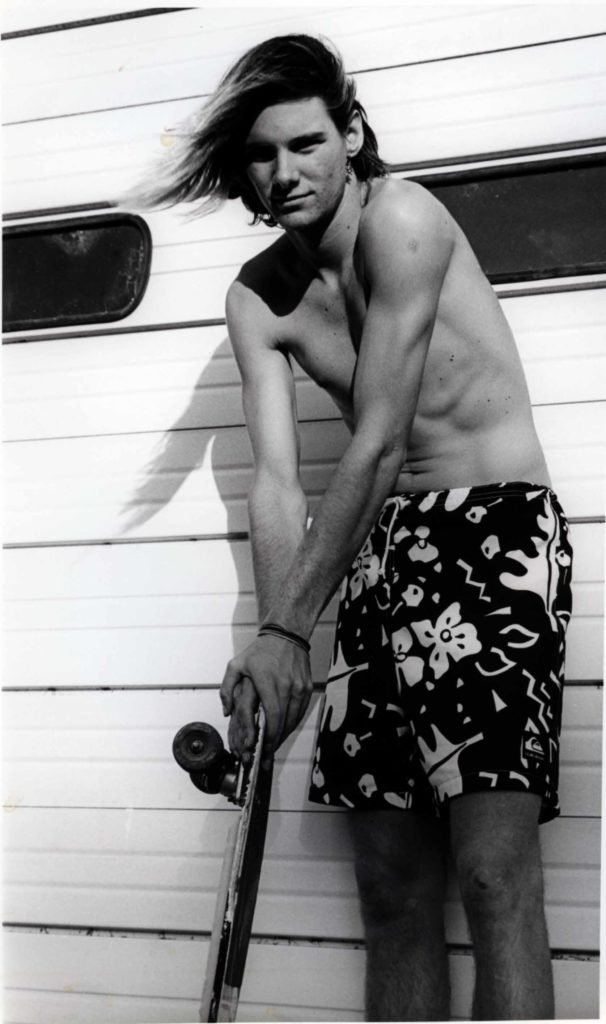

Early 80's Kevin Staab. Photo: Grant Brittian

LMB: The adrenaline is worth it. Why was Tracker so important in the history of skateboarding?

TH: Tracker was important because they were there from day one, obviously, and became a standard. In the later years, they came to represent a certain style and ethic of skating, and also even geography. At some point, Tracker was Southern California—that’s where we lived, that was our life. It came to represent so much more than just an original truck. We had a crew.

KS: I wanted to ride for Tracker because of the Bones Brigade guys. Straight up, that was it. Those were the raddest guys.

LMB: At one point, so much of the Bones Brigade was on Tracker.

KS: Wasn’t it pretty much everybody at one point?

LMB: Yeah, I think it was everybody. In 1983, I was going to come out with TransWorld Skateboarding magazine, and Stacy said, “Oh, man. We’ve got to change it up. I’ve got to put some guys on Indys or we’re not going to get coverage in Thrasher.”

KS: The Indy Thrasher magazine and the Tracker TransWorld magazine were catalogs for the companies.

LMB: So, which tricks did you guys invent on Trackers?

KS: (Speaking to Tony) Are you going to run with that? I’ll take a break. I’ll be back in a few minutes (laughs). I’ve got the blunt.

TH: Yeah, he invented the blunt on Trackers. That’s pretty monumental right there. Fakie Ollie. I did the tricks I’m most proud of—most of my monumental tricks—when I was riding for Tracker: fingerflip air, backside Varial, Madonna, 720, and all of the different 540 variations. There are all of these little tricks that I don’t even think about. I’m trying to think of the ones that had longevity, like the stalefish.

LMB: You really pushed the level of skating with the fingerflip, and people thought, “Oh, yeah, that flippy stuff. Whatever.” What made you think of doing something like that?

TH: I did fingerflip airs because I was watching Rodney Mullen. He was such a master technician on the flat. I always wanted to figure out how, because he only had a few inches of air time to do a trick, and we got four or five feet of air time. Well, if he was doing it that close to the ground, it was obvious that we could do it above coping. We just had to figure it out. That was my motivation, for sure. And then it went the other way. I learned Airwalks, and then he started to do Airwalks on the ground, which seems way harder to me because you have no time.

Early photo of Tony by his older brother Steve Hawk

LMB: Did you try those tricks on the ground first?

TH: No, I was the worst freestyler. I had what I considered vertosis: I did everything when I was skating vert. So, I had to go with my expertise. But, some of the stuff was obviously inspired by what Rodney was doing. All of the flip tricks, shove-its—anything without grabs—was all inspired by freestyle, mostly Rodney.

LMB: You and Christian really put on a show in the ’80s. The most memorable was the explosive runoff between you guys at the Vision Skate Escape. It was intense. Christian was flying higher than ever, and you were doing back-to-back tricks like there was no tomorrow.

TH: Yeah, it was fun, the whole era when people were pitting me against Christian. We were actually friends, it just became that you were tricky and technical, or all style and air. To be honest, I only had a couple of friends who were into the trick thing—Kevin and Lester—and that was our crew. All we cared about was new tricks. We didn’t care how you looked doing them. We just knew the difficulty factor of it. Christian was all style. It was so apples and oranges for judges, and there was always controversy. But, no matter who won, it didn’t matter. The Skate Escape was the culmination of that because all I had was tricks, Christian had the airs and the style, and we both pretty much did our best, the epitome of what our styles meant. At that time, it was so subjective. I didn’t really care. I was stoked. I wish I had made my last 720. I still think about that sometimes. I kind of made it—I slid off the ramp. But, it was so incredible to be on that kind of stage, because that was the biggest event ever at the time. It was a sold-out arena for a skateboard competition, which was unheard of.

I went to South Africa three or four years later, and the Skate Escape had such an impact on them, they recreated that ramp for a demo, with the spine, the mini-ramp and the same kind of venue. They flew Ray Barbee and me there and Ray did flatland demos in front of the ramp. I’m not kidding. I think they had a jump ramp for him in front of several thousand people. They were just so excited about the idea of skateboarding and the spectacle of it and that whole scenario, that they recreated the whole Skate Escape thing for two dudes. And they did it because they watched the video, and saw how big it was. And to their credit, they had the same size crowd. It was crazy.

LMB: It’s interesting to watch the progression of skating. I started skating in 1958 on steel wheels, and then through the ’70s with the new urethane wheel, ditches, transition, and swimming pools came in. But, you had to go through this huge learning curve of how to ride and even to fall. Then in the ’80s, Stacy started releasing the Bones Brigade videos, and skaters could learn tricks much faster than before because they didn’t have to figure out how they were done. We went to a contest in Texas and Stacy said, “Look at those kids on the ramp.” He was wondering if his videos got around and made an impact, and there were some kids on the ramp with their Powell-Peralta boards and their heads tilted like Cab. Tony, how many times were you world champion?

TH: The NSA had the official scoring system from 1981 to ’91, and then it kind of splintered away and became all random events. There weren’t actually very many events, there were a couple, sometimes with pretty minimal prize money, but that’s all we had.

1996 Tracker Ad

GSD: Did you keep all of your trophies?

TH: I don’t have any trophies.

GSD: Did you just chuck them out or give them away?

TH: I usually gave them away at the event. Part of it was because I didn’t want to look back all the time. I just always wanted to keep progressing and looking forward, so I didn’t want to rest on these previous accolades. But, there were also these obnoxious BMXers who would pose with a million trophies behind them, because they had a race or two every single weekend, and they placed third and got a trophy. I remember seeing those photos in magazines, and I thought, “I don’t ever want to be one of those dudes.”

LMB: Did you keep the TransWorld trophies?

TH: I have kept my TransWorld ones. I kept anything that was unique and cool looking. But I got rid of any trophy with the corny skater pose.

GSD: There was a Powell ad about that.

KS: I remember Stacy saying, “You’re not standing right, Staab.”

TH: They had a trophy made for me to look at.

KS: I think the only trophy I saved was the Turkey Shoot trophy. I was going through the trophies and I had to save that one because it has a turkey on it.

LMB: So, you guys rode the Trackers with the nylon baseplates. Did you ride your trucks really loose at the time?

KS: My trucks didn’t turn, ever, so it didn’t matter what I was using, because I rode super tight trucks all the time. I remember driving six hours from Arizona, getting to Del Mar, being totally stoked, bailing on my second air at night, my board going down and watching the baseplates just shatter as soon as it hit the cold. But, in Arizona, it was great, because they just twisted and bent all over the place. I was just so excited to have something so light. I had the magnesium hangers with the plastic baseplates. Then the Copers came out, and they came in all of those colors.

TH: Then you balanced out all of that weight loss with all of the plastic accessories, like Nose Bones, rails, Lappers and Copers.

1988 Tracker ad with Hawk and Staab

GSD: And Tail Ribs.

TH: No Tail Ribs, that’s where I drew the line.

KS: Nose bones were fun.

TH: They were pretty good.

KS: I put those in boiling water or the microwave to bend them, like making spaghetti. But, if you were off by three seconds, the thing started popping and bubbling.

LMB: So, you never tried the toaster over?

KS: No, I was smart enough to stay away from that.

TH: The nylon baseplates were the perfect bad storm scenario in that when we’d skate Del Mar at night, the wind would come off the ocean and it would be so cold that those things would get super hard and break. I broke a ton of them at Del Mar. They wouldn’t break anywhere else, but I broke a ton at Del Mar. And I’m the same as Kevin; I kept my trucks so tight because I like to think we’re going faster than most people, so we needed that stability. So, I kept my trucks super tight, and when something would go wrong, the baseplate would just break.

GSD: Did you skate Tracker aluminum or magnesium baseplates at any point?

TH: Magnesium, yeah. When we were growing up, magnesium was the holy grail of trucks, because we couldn’t afford them. It was like, “Oh, you have magnesiums? That’s amazing.”

KS: As soon as I got my first pair from you (Larry), I didn’t want to scratch them, so I put Copers on them right away.

Lance Smith: Did you guys feel the weight difference?

TH: Yeah, I think we did. You got so used to clunky, heavy boards that anything different was good and was noticeable.

KS: But, riding Cubic wheels…

TH: Yeah, those massive wheels, rails, and my dad made me plexiglass rails that were three inches thick, my board was so heavy, I don’t understand how I ever got it off the ground.

LS: When you put on those rails, they rattled. Jeff Tatum called them rattle buckets.

KS: Yeah, rattle buckets. I think my board still sounds like that.

TH: Yeah, but that’s if you didn’t know what you’re doing.

KS: I’m still rocking rails. Dude, I used to sell TransWorld. You used to send them to my house, and I would walk around my block and try to sell them.

LMB: Did you offer a discount?

KS: No, it was my first and only job. It was just weird, “Hey, I know you guys don’t skateboard, but do you want to buy this magazine. I’m trying to get it going.”

LMB: Cool. Thank you.

KS: You’re welcome. I like to think I had a part in it all.

GSD: Kevin, on that first TransWorld cover you got, did you make that tweaked out frontside air?

KS: Yeah, because it was off the extension, so I had to grab early. Grant Brittain asked, “Oh, have you seen the cover of the new mag?” He handed it to me, and I was like (big eyes). “I got the cover. Like, wow!” I was freaking out.

GSD: Some people thought it looked like a bail shot.

KS: No, it wasn’t.

TH: If you took a picture of Kevin doing any frontside air, it would be up for debate if he made it.

Early photo of Kevin

GSD: How did you come up with that pirate theme for your Sims decks in the late ’80s?

KS: Because of all of the characters I liked as a kid, pirates were always one of my favorites. It was kind of like, “After the mad scientist graphics on Sims, what am I going to do next?” I had it in my head that I wanted to do a pirate. The first artist made it look too realistic for me, and I didn’t want that. It was almost too evil. I wanted it to follow the cartoon feel of the mad scientist, but I also wanted the pirate to look like the singer of The Cult, so that’s where that came, too.

GSD: You just predicted my next question. When you grew your hair down to your waist in the late ’80s, did The Cult or I inspire you?

KS: That would be the singer of The Cult.

GSD: Tell us about your band Ice Cream Headache.

KS: The best was going to Vegas for a show we had there, and I didn’t know Tony was going to do a demo.

TH: Behind the band.

KS: Behind the band. That was crazy. I just remember that you said, “Dude, you have long hair and a weird beard.” And I hadn’t been skating very much.

TH: He was not skating. He was way better at drinking than skating at the time.

KS: I always wanted to play music, even though I was skateboarding. I always had the idea that I would have rather been a musician because then I would put in an hour a day making twice as much money as I would ever make skateboarding. But, that didn’t end up happening—it ended up going the other way. Skating went well, but I always wanted to play music. I have a lot of friends who actually dropped out of skating at a younger age and got to be musicians. So, it was just a matter of time before we put something together. During that time, I had a clothing company called 90, so I really wanted to market the idea of Ice Cream heartache with really cool t-shirts. I sold so many t-shirts to Japan that it funded the release of two cassette tapes.

GSD: I was going to say I thought your albums came out on cassette.

KS: Yeah, they came out on cassettes. CDs didn’t happen yet, so cassettes were kind of cool. We did that and had a lot of fun. I had a good time doing that for about five years. Later, I was in touch with Tony a lot more often, and he said, “Dude, just get out of Arizona and move back to California. There’s a lot of good stuff to skate.” I actually had a band room at my house, my backyard pool was empty, and I was skating it all the time. But, I was just grinding and keeping it going. It wasn’t like the way I wanted to ride, still doing airs. But nobody rode, and there was nothing to ride out there, so I kind of wasn’t it doing much for a period of time. Then Tony lit a fire under my ass and got me back out here. Seriously, I played a Wednesday show, packed all of my stuff, left that following Saturday, and never went back. That was it.

GSD: What did you play in the band?

KS: I was the singer in the band. Why would I be the singer, right? I could be the crazy, entertaining guy, I was not that good of a musician, but I could yell pretty good, so they liked that.

GSD: I remember in the ’80s when CDs were first coming out, we were in a hotel room at a contest and Tony had some CDs. You grabbed one of them, took it out of the jewel case, and said, “Yeah, I’ve heard of these new CDs. They’re totally indestructible!” and you just winged it across the room. Tony obviously got pissed.

KS: Sorry, dude.

TH: All of my CDs ended up getting scratched. I would just put them in my bag not in cases, just free floating, because they said CDs were indestructible. Then I’d get to an event and they would all skip, and I was like, “What are they talking about, indestructible? These scratch just like records. This is terrible.”

LMB: Tony, you came to Tracker and explored the idea of starting your own board company with Lester and Adrian. When was that?

TH: Yeah, sometime around 1987-’88. Powell thought I was diluting myself by doing all of these sponsorships, so they were frustrated with me. Christian Hosoi had started his own thing, and I was like, “Oh, I could do that.” So, you and I were talking about working together on it. I started taking it pretty seriously. Then at some point, I realized I just wanted to skate. I didn’t want to be responsible for a company’s direction or make the decisions. I appreciated the opportunity and the fact that you believed in me, but I just wasn’t ready for that yet in my skating career. I loved the actual skating way too much, and so I went back to Powell with my tail between my legs. “I’m sorry I even thought about this. I’d rather just skate for Powell.” “Well, you’ve got to drop all of these other sponsors and endorsements that you’re doing,” which meant fingerboards, backpacks, and all of this random shit that I’d signed off on. So, I did and got sued by one for breach of contract. But, it was worth it to me to be more focused and to be respected more for my abilities instead of being known for my exploits.

Hawk photo by Grant Brittian

LMB: When did you start Birdhouse?

TH: We started Birdhouse in 1992 because I could tell that my career as a skater was fading. Being a vert skater was impossibly hard at the time plus I wanted to start a company with my own direction. Things were getting weird in the industry. Steve Rocco was dominating, and it was all about talking shit on other brands to make your brands seem cooler. I didn’t want any part of that, and Powell got caught up in it. I just wanted to promote a brand through good skating, not through sarcasm. I wanted to do it because it was fun and our guys were good, not because we were good and they sucked. That was my inspiration for starting Birdhouse, and the main skaters on Powell were all doing their own thing anyway. Lance and I left together, and I partnered up with Per Welinder, who had left as well. So, the timing was right, and little did we know when we actually decided to do this that Stacy had already left. We didn’t even know that. He hadn’t made it known.

LMB: They’re working on a book up at Powell, too.

TH: Yeah, the thing about the Powell book is it ends before what I’m talking about. So did the Bones Brigade doc. It was kind of like, “Yeah, it was fun, then it was over.” They don’t talk about how things went awry. It’s got a little happy bow on the end. “Yeah, we did it!”

GSD: Did the Powell doc mention the Rocco thing in the end?

TH: A little bit. At the time, Stacy wanted to fund our companies, but George wasn’t really into it. When we started Birdhouse—I’m going to get in so much trouble—we had already sourced everything, and we were doing it ourselves. Then George sent us boards with the Birdhouse logo we created—production skateboards. We didn’t talk to him at all, he just did it. So, we got these boards and it was like, “What is this?” Per was like, “I guess George made those for us because he wants to manufacture them.” “Okay, we’re just going to pretend we didn’t see those. We’ll put them over there and go on our way.” He lifted the logo from an ad that I made.

GSD: It was all pixely.

TH: Oh yeah, not that my ads were all high-res or good in any form in the beginning. Yeah, that was weird. We patched up all those things, but at the time, it was strange.

LMB: Well, George is an extreme idealist tucked away up in Santa Barbara, and he wants the world to be the way he thinks it ought to be.

TH: He’s definitely eased up, and hooking back up with Stacy has changed his views a lot.

LMB: Yeah, it was pretty cool to see all of you guys on stage at that premiere up in Santa Barbara.

TH: I didn’t go to that one.

LMB: Oh, you weren’t there? Well, Stecyk, Stacy, and George were all on the stage together. Anyway, just like Stacy left G&S and started Powell-Peralta with George, you grew up…

TH: And the same things happened to me. Andrew Reynolds was an amateur and left Birdhouse to start Baker, and ended up sponsoring my own son. All of that stuff comes around.

1998 Tracker Hawk truck ad

LMB: So, we have the Tony Hawk truck here that Tracker made for a while. You had an amazing team.

TH: Yeah, I was really pretty proud of this truck. You know why? Because it still looked like a Tracker truck, but it was iconic, and a lot of people associated that with the T [on the truck’s face]. I just thought it was cool that we managed to take advantage of the Tracker design, but altered it enough so it was iconic, but still identifiable as a Tracker. That was fun.

GSD: Did you work hands-on with Larry for the design?

TH: I knew Larry had ideas for new trucks, and putting my name on it was good for changing it up fairly drastically, so I trusted his instincts on that. I was more into the graphical design of it, how this would show up and this would look. I mean just using that lettering was no joke with trying to get this approved by Powell, but we did it. To be honest, when things were pretty rough for me financially in the mid-’90s, this truck saved my life in terms of being able to pay a mortgage, eat and raise a family.

Kevin talks about the Tracker Staab Truck. Photo: Lance Smith

LMB: Kevin, tell us about your Tracker Staab truck.

KS: Buddy Carr said, “What do you want? I can wrap a truck for you. What’s it going to take for you to ride Trackers again?” I said, “Make me a purple truck.” So, he made me one and I rode it. Then he said, “We can do an awesome wrap. What do you want to do?” I told him we either have to use a leopard print or a pinky purple color with pirates on it. I was just stoked when he sent me that sample, and, as far as I know, they sold out pretty much immediately, because I never got a second set. So, I was super stoked.

LMB: I drove down to Buddy’s to get that truck because I don’t even have one.

KS: Seriously? Collectors and people like that are holding onto things that are coming out again. I think that a lot of them were the ones who ate up those things right away or the European dudes.

LMB: It was super expensive to do that. I don’t know if we could recreate it now.

KS: I think it is super expensive because I don’t see anybody wrapping trucks like that now. They’re usually just printed. I was just honored that it happened. Buddy let me know that it was going to be a little more expensive and Tracker would make a little less, but I just wanted to see it happen.

LMB: Do you recall any memorable times with the Tracker team?

TH: One of my funniest memories was when you approached me because you thought Lapper sales were slacking, and said, “We’ve got to do an ad with a Lapper.” You had this state-of-the-art Corvette, and you asked, “How about if you do a street plant on my Corvette, then hang up on it?” As a skater, I knew that just wouldn’t work at all. But, I thought it was a hilarious idea. “First of all, I’m going to trash your car. Secondly, you can’t really make that.” I didn’t know how that would highlight the Lapper anyway. You brought your car to my house, and I figured I could Ollie off the trunk of the car into my jump ramp, hang up on the jump ramp, and come in with a Lapper. That actually worked pretty well, as cheesy as it seems now.

LMB: We put some tape down on my trunk.

TH: The other thing with Powell was, as Powell riders, we weren’t allowed to be in other videos. There was a ban on shooting anything for anyone else. But, the loophole that Ridge figured out with Stacy was that if you shoot them at a contest, then it’s okay because it’s a public viewing anyway. I always wanted to be in Tracker videos, and I always wanted to have good footage in them. I didn’t want it to be a contest run, so in practice for contests, I would purposely get Ridge on the ramp and shoot just tricks. That was my way of following Stacy’s orders but actually getting footage for the Tracker videos. So, all of the early footage is of me just skating contest ramps, but I was doing some of my hardest stuff just for that video. It was stuff I wouldn’t do in the contest because it was too hard. So, that was my way of getting new footage.

1987 Tracker Lapper ad

GSD: So, was that in the late ’80s?

TH: Yeah.

LMB: The Brotherhood was a huge one.

TH: Yeah, but that’s what I can remember vividly because I so badly wanted to be in a Tracker video.

LMB: How about you, Kevin?

KS: It was just that all of my friends were on Tracker. Tony is my best friend, and then it was, like, Lester Kasai, Joe Johnson, and Ray Underhill. We were such a close-knit group, and Ridge always had us do everything together. And when you look at all of the ads that were popping up all over the place, I know those are the things going in the book and those are the times I remember. “Hey, we’re going to do an ad today.” It was always something goofy, and it was always fun to be part of everything that was going on.

TH: And, for the most part, we all lived together. My whole household was Tracker. I lived with Ray and Joe. Kevin would come and stay. That was it. We were the Tracker Del Mar crew.

KS: It was a brotherhood. You wanted to be on the same team all of your friends were on.

LMB: So, which trucks are you riding now?

TH: I went through a couple of sponsors after Tracker. Fury. That’s what happened. I try to erase Fury from my mind. So, basically, after Tracker, none of the guys I knew were on Tracker, and Per Welinder, my partner at Birdhouse, wanted to help start a company, so we started Fury. We actually funded it and it went okay for a little while, but all of the main riders left. Then I got a chance to ride for another new company, Thieve, but that didn’t work out at all. I rode for Thieve mostly because all of the people I knew at Tracker were gone, and I had an opportunity to help a start-up. I was excited with the success of Birdhouse, so I decided to do that with a truck. That ended up not panning out very well, so I went to Indy because that’s where I started. I wasn’t looking to get deeply involved with a truck company again. I just wanted to be a rider. I didn’t want to have to worry about the promotions and stuff like that, so it’s kind of nice to be one of the crowd with Indy. I’m just one of the gang there. My relationship with Tracker was one of my longest sponsorships ever.

LMB: We’d like to have you back.

TH: (Laughs) I’m pretty happy just being low-key.

LMB: We want to use you on the cover of the Tracker book. You’re probably the most iconic skater throughout all of those huge years that Tracker had. What are your thoughts on that?

TH: It’s really your discretion. I don’t have any control over that. I wouldn’t be opposed to it. Even the Indy guys know I’m identified as a Tracker rider. In fact, the funny thing is, I did a welcome video for Indy. There were a couple of comments like, “Does this mean that Indy is going to start making pink trucks?” But, it’s so far past any of that; I think it’s more of a joke like Fausto is rolling over in his grave. Fausto was one of my biggest supporters, even though I was on Tracker. He used to give me advice. I remember him yelling at me at Colton. He was scary to me. “You need to hit the coping HARD when you go in there. Don’t just float around. GRIND it.” I was like, “Okay, yes sir. I’ll do that.”

LS: This was the shot we were thinking of.

TH: Oh yeah, I love that photo.

Miki, Tony, and Kevin talk about the Tony Hawk Foundation. Photo: Lance Smith

LMB: So, you guys have been promoting the sport with your Tony Hawk Foundation. You help build skateparks all over. What’s your mission statement?

TH: To provide public skateparks to low-income areas, and to empower the youth in those areas who want to get the park going themselves. We don’t just come in and say, “You guys need a skatepark in this area, and we’re going to build you one.” We help the people who have started the process because we want them to feel a sense of ownership and pride, and not just take it for granted. The foundation has been around for 12 years now. Miki is by far the most qualified and the most passionate person to be the director. He and I were the only two skaters at San Dieguito high school.

Miki Vuckovich: Tony and I met at a skatepark, Del Mar Skate Ranch. What we understand about skateparks is intuitive. For us, the goal is to try to quantify that and translate that for people who haven’t had the experience we’ve had, and understand that the community that develops around a skatepark, the camaraderie amongst the skaters, the difference between having a place to call their own and having to skate around the streets and find their own places. It’s night and day. We know from our personal experience the impact a skatepark has on the kids’ lives. It’s just tremendous convincing communities and helping local advocates to share that message, and to articulate that message is really the key for us to help push those projects forward.

GSD: What are your duties at the Foundation?

MV: Sweep and answer phones (laughs). We’ve got a terrific staff. We’re a small group of about five staff members. My main job is working with each of them, whether it’s in the development side or the program side, making sure they have what they need. I keep things on track with Tony and the Board of Directors, what they want us to do, the decisions that they’ve made, and the projects that we have going on. We set things up for the future to help grow and promote our mission.

Photo: Lance Smith

LMB: How do you fund all of this?

TH: Funding comes from some endemic sponsors, some of my same sponsors, and, as a skater, I donate money to the foundation. We do one big fundraiser a year called Stand Up for Skateparks, which is a big family-friendly event with bands, auction items, and a skate demo. We usually raise between $700,000 to a million just from that event alone. Now we’re on the radar of bigger philanthropies, so we’re applying for grants from bigger foundations. We also just won a sports philanthropy award from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, which really gives us a sense of legitimacy in the eyes of big foundations, because skateboarding was considered more of a novelty. They still look at it like that. After all of this time, after all of the X Games and the success, they’re like, “Skateboarding? Kids will outgrow that.” Skateparks are used from sun up to sundown 10 times as much as any other sports facility or public free space, including baseball fields, basketball courts, and tennis courts.

MV: In every case, every skatepark we’ve helped open has immediately become the most popular facility that the city has ever created, and it’s always, “Oh, I guess we built it too small.”

TH: They always end up wanting to do more.