Complete Interview of Tommy Ryan

Tommy Ryan Interview

By Larry Balma

Tuna fisherman quit to be a pro skater, then horse trainer in Mesquite, Nevada now he’s back at the beach in Hawaii. Photo: Glen E. Friedman BurningFlags.com

Where are you from? When did you start skateboarding?

I was born and raised in Ocean Beach, San Diego, California. I graduated from Point Loma high school. I started skateboarding in the early ’60s. If you do the math, it’s been about 55 years.

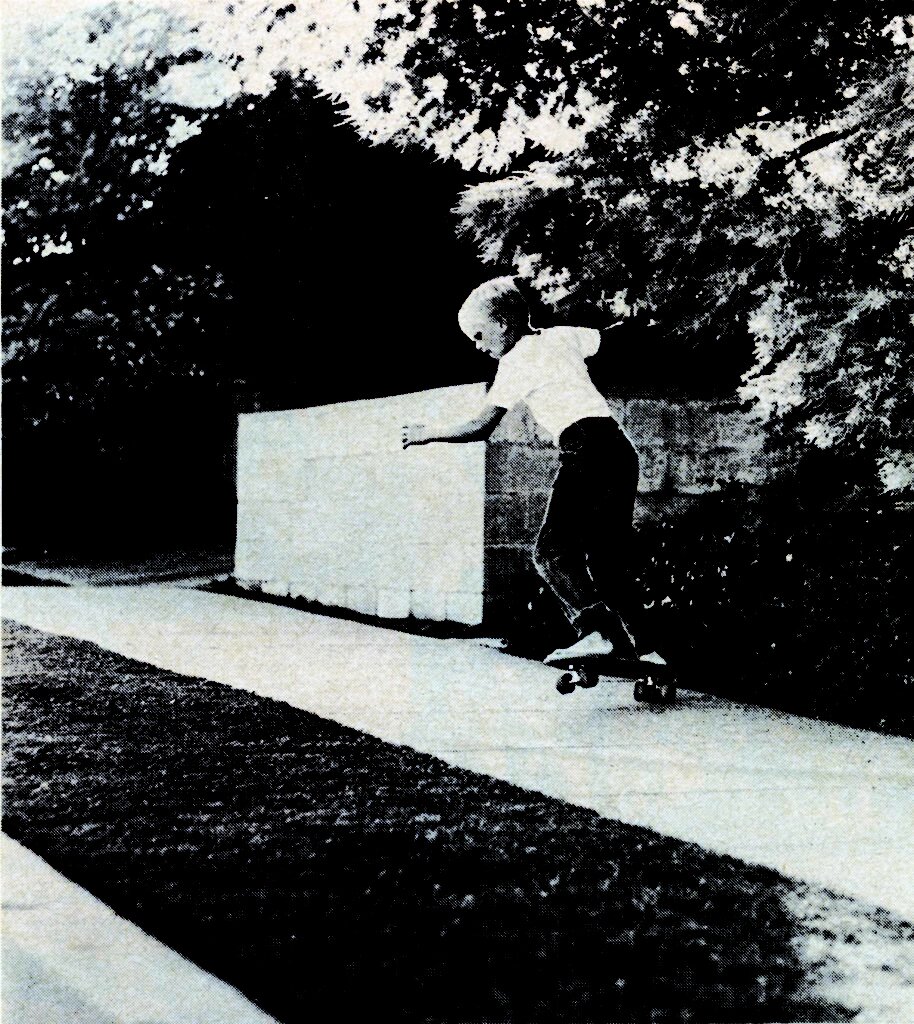

Young Tommy Ryan

Did you surf before you skateboarded?

I surfed. I came from a heavy surfing family. My dad surfed, my brother surfed for G&S. We grew up on the ocean. My Dad was a lifeguard. We surfed, skated, and didn’t know much else. That was our life growing up.

So, from surfing, you got turned on to skateboarding?

It was a funny thing. We would go roller-skating and we saw the old skateboards with a wooden box on the front. They would take a wooden box and make a scooter. That’s the first thing I remember, going from the scooter to the skateboard on a 2x4 right during the era between metal wheels and clay wheels from the roller skating rinks. I remember having my parents take us down to the rink, and we would buy those wheels and hacksaw them in half. Those were really the first clay skateboard wheels that I knew of. I was around 10 years old in 1961-’62, and everyone thought we were crazy because the scooters were on metal wheels with a crate box. That’s how it started for me.

Is your brother older or younger?

My brother is four or five years older than me.

So, when you were building this stuff, he kind of mentored you along the way?

It was a family thing. We both skated, we both surfed. My Dad was a musician in San Diego. We grew up in the ocean, surfing, skateboarding. You would go to the surf movies and see these old guys riding skateboards. It was just a natural phenomenon to do it. I never realized I would be here at this point in my life talking about skateboarding. It’s lasted my whole entire life.

Tommy Ryan surf style at Carlsbad Skatepark, CA. Photo: Chuck Edwall

So, Larry Stevenson started off the skateboard craze with Makaha, and he was a Venice lifeguard, then the surf companies picked up on it as a marketing thing and you ended up on G&S on the skate team. Tell me about that.

Actually, it started with the Continental Surf Skater, the first board after the metal wheel era with Chicago Trucks. This board was distributed to every Montgomery Ward store in the US, and I toured for maybe three years, going to every one of their stores across the US to promote that skateboard. The company went as far as it could go, then G&S came out with the first Fibreflex. Denis Schufeldt, Skip Frye, my brother, and a couple of other guys I can’t remember approached us. I remember Skip Frye was my hero, as a surf guy, and getting to skateboard with him was a no-brainer.I remember my parents saying [regarding Continental], “You can’t leave this company. This is what got us here!” I said, “No, this is Skip Frye, the guy I want to skate with.” About a year after we did that, we went to the first Anaheim skateboard contest, and I said, “Man, I’m traveling with Skip Frye and my brother. This is really cool.” It was still like riding a wooden board. It wasn’t a true flex board. Maybe I wasn’t heavy enough to make it flex, but they called it a FibreFlex. We were the first G&S skateboard team ever in existence, so it was pretty neat.

So, that was around 1965?

Yeah, it was probably around 1965. I was 13 or 14 years old. I remember going up to Anaheim and seeing all of these big name surf guys riding the big wooden ramp they had built in the stadium, going around cones. I didn’t know what slalom was, but it was really cool.

Let’s jump back to the Continental Surf Skater. They made their own truck, and it’s actually three inches wide. I had never seen one of those.

Chicago Trucks had such a corner on the market. They sold trucks to Makaha and the red Roller Derby board. The Continental truck was made in Del Mar at the old train station. They had some guy in there with a metal press. I remember riding it for the first time, and I said, “Wow! The center of gravity is higher.” I think that was when it really hit me that skateboarding wasn’t just going to be four wheels and a board. Skateboarding was going to start taking some different turns. Not too long after that, the first urethane wheel, the Cadillac, came out. That was one of the first jumps out of the Chicago Trucks and wooden board era.

How did Continental decide to get into the business?

There were a couple of surf guys up in North County who had money in the company to make it. My dad got involved in it, and he was kind of my manager. We had done a few local contests, but Continental was a one-trick pony. They had an oak board with some stripes on it and Chicago Trucks. Later, when Chicago couldn’t build enough trucks for every board company, we built the Continental trucks. Then Continental pretty much had folded not long after I went to G&S. Dale Dobson rode for Continental but then he pulled out. Then some other guys bought it. I don’t know, I was so young. It was one of those things—a lot of money was made, but I didn’t make any.

Tommy Ryan, one of the inspirations for the Tracker Racetrack taking it through the cones at La Costa. Photo: Larry Balma

So, then you skated for G&S, and the FibreFlex evolved into a more flexible board. Then the urethane wheels came along, which really made it work. Where did you meet Bobby Turner?

Bobby Turner worked for G&S as a surfboard glasser. I met him at the old G&S shop out in Rose Canyon. We were out there one day looking at the surfboards with Floyd Smith and Sobe, who was their head salesman. He said, “Hey, I want to show you something out in my car.” He brought out this board, and I’m not kidding, it was 32 inches long with a full nose and a cut-away tail. He said, “I want you to stand on this and see how much it flexes.” I said, “Wow! This is really cool.” I told him I lived up in Del Mar and that we skated a ton of streets. “We don’t ride cones, we’re street skaters. There’s a whole clan of us who live up off of 15th street. We go to the top of the hills and bomb down them every single day.”

So, one day, Bobby brought a couple of boards over to the house. The first thing I said was, “Well, if they were a little fatter,” and if they were this, that and the other. Then we started talking about this reverse camber. Any boards that had any kind of flex would snap. “Well,” he said. “I know how to fix this because I build surfboards with resin. I can’t give away the secret, but there is a formula to make these boards flex. So, we talked for hours, then he came back the next day, took a couple of runs with us, and I said, “If you can, make the boards a bit wider because the wheels rub.”

So, Bobby came back a few days later, and he got it almost identical to what we talked about. We rode this board and we went, “Wow!” But, I rode for G&S. He said, “I can make these boards with more camber, more this and that. Come over to my shop and we’ll talk about it.” Sure enough, we went over to his little shack in Sorrento Valley, and it was like nothing you’ve ever seen. He had these molds, and that’s really how the Turner Summer Ski came about. From that day on, I was really interested in making the sport better. Then slalom racing came in, and that’s where the Turner Summer Ski started. After about a couple of months of me talking to Bobby, we came out with the first cut-away and full nose, which really set the standard in racing. It’s different now, but back in the day, this was the racer’s choice. That board was what everyone wanted to ride.

We would go to these contests, and what was so ironic about it was that we were riding on these arena floors, like, “Okay, come down this ramp and go around these 15 cones, and you’re the winner.” Well, after doing this for years, we knew it was so lame. We street skated, so we started setting up cones on streets with some downhill runs, and, all of a sudden, a new sport was developed. Slalom had been happening in these bunk arenas with people trying to promote themselves or make money. So, La Costa was born. We raced every Sunday, and the equipment kept getting better and better. It was all about bringing your equipment and sharing ideas. Slalom really started at La Costa. With Tracker and Turner, we developed boards that felt the hill vs. just standing there and steering down the hill. We were innovating a sport: tight slalom, giant slalom, which came right out of the snow ski industry. But, all of a sudden, our boards flexed and we had traction. We had a different take on skateboarding in general.

Where and when did you get your first Tracker Trucks?

I couldn’t tell you the day, but I was lucky to be involved from the very beginning with Dave Dominy and you. I remember coming back from fishing, because I was a commercial fisherman then, and you had a couple of prototypes. You handed me a pair and said, “Put these on your Turner board.” They were the Fultracks. I rode them and could not believe— because they were so wide—the traction I got with these little Cadillac wheels. I could actually grip the urethane on the asphalt. I said, “This is it. Skateboarding is going to change again.” Between the urethane wheels, the Tracker Trucks, and the flex, a sport was all of a sudden created from our equipment.

We always told people, “Let’s set up a course—no money, no nothing. Just come up and race.” At first, everyone said no, then it turned into every Sunday. It was major. The hill was crammed packed, which also gave us another tool to sell our equipment to get our name out. Tracker was there, and it was a cool thing because we would give you guys input, and almost immediately, Larry would go back to the shop and shave down the truck a little bit. I think the Midtrack was developed because we wanted a little bit narrower track so we could do tighter cones. We were changing back trucks to front trucks—changing the equipment to meet the course. No one would show up there without five boards, 80 sets of wheels, 20 sets of trucks, changing this, changing that. Those were some good times and good days of racing.

Tracker was a big part of changing the way skateboarding was going because the trucks made before then were too narrow for street skating. But, Trackers gave so much traction, and you could get the feel of the board and the turns because the trucks would track. We didn’t ride with shoes—no grip tape, no nothing. We would just stand there barefooted and hang on. Then, all of a sudden, we had track, we had grip, we had all of those things. Skateboarding would never be the same ever again from those days to now. You guys have been around for 40 years. Lance Smith and myself have been there since day one. I feel that we were the original guys. We owe Tracker a lot for what you guys have done for us. I feel really good about it.

I remember working really close with you on the R&D of the trucks. In fact, I developed the Tracker Racetrack truck just experimenting with geometry. You were on most of the prototype trucks we made before anybody else.

That was the beauty of it. I had the inside track because we lived close together. My mind was always thinking about, “How can we better the sport? How can we better the equipment?” I spent my whole life trying to make the sport better, trying to innovate the equipment. I rode for only two companies my whole entire life, which were G&S and Turner. Continental Surf Skater didn’t really have a team, it was just me. I was the only team rider, but the first two teams were G&S and Turner. Of course, Tracker was one of my big sponsors. I think if Tracker wouldn’t have come along, then at that point in time, with the way the sport had revolved around the equipment, that’s why it’s here 40 years later. That’s why, because you were there on the ground floor, we did so much. I remember you’d cut down the trucks longer on one side like the racecars. We’d cut down the axle, we’d try stuff that no one would have the access to the equipment to do.

Let’s talk about the speed runs at Signal Hill.

Signal Hill was once in a lifetime. It took the sport to another level. There were only a handful of people who really did it back then, and, again, equipment played such a large part in how fast you could go on a skateboard. We went to Tracker and asked for bushings that didn’t turn because we wanted to go straight. We tried hundreds of different set-ups, whether we needed a longer or shorter wheelbase. This is one of the boards, and these look like some of the prototype Tracker trucks. Yes, these are the ones with the little flanges. We changed that part of the trucks to make a flatter flange so the stiffer rubbers would sit flatter, then they wouldn’t rock. We’d keep the front truck really tight and the back truck loose.

At Signal Hill, I did 53 mph on my knees, and I would love to say that I probably did 75 mph—close to 80 mph—off the record. We would do tow-in rides at La Costa and hit way faster than 50 mph. But, the way Signal Hill was set up, you could only push to a certain point, and 53 mph was as fast as you could go, or 56 mph in the skate cars. This board here was designed to stand up on, but the way it was so stiff, it would have a mind of its own. It would go straight and your body would go another way. So, at those speeds, we decided to hollow out this deck and ride on our knees, which made the speeds unlimited. You could go as fast as you possibly wanted to go in a kneeling position. You could get down in a low tuck. It had a little bit of a reverse camber, designed so when your weight came down on the board, the weight would release, and that was what made the board ride so well. The reverse camber was always a release to make it accelerate.

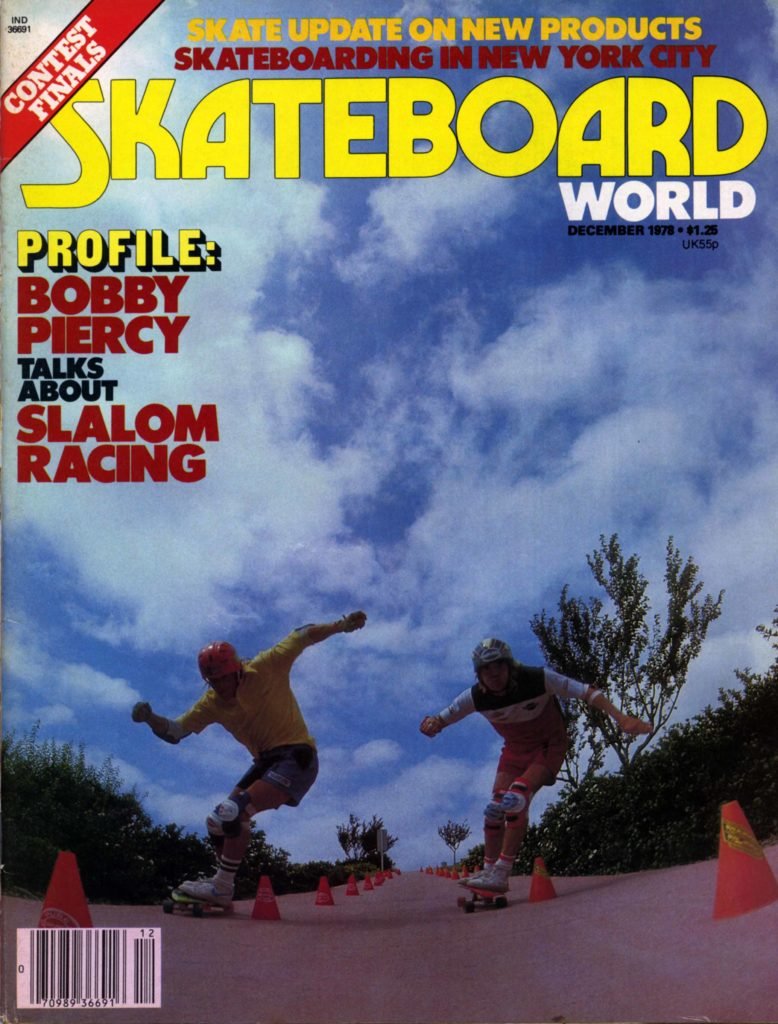

1977 Tracker Ad

Bobby Turner had experience in downhill skiing, so he translated that into the skateboard.

Right. The way the skis would flex and the reverse camber. He was so far ahead of his time because everyone was thinking of flex underneath the trucks. We always thought that snow skis were developed so when you release your weight, your skis will bow to a point when you can push off of that flex. Bobby took that same design, and with my input, we developed the two boards together. When you ride on a floor, you dry pump on the board. On a flat board with no flex, it was really work to keep the board moving. But, with our boards, it was effortless. It was flex and flex, and the board would release with your weight. So, then the boards came down to how much do you weigh? It depends on how much the boards flex. Which again was so far ahead of its time. There was nothing like that on the market and there are still very few to this day. They had reverse camber because the courses changed and technology changed.

But, when we came down Signal Hill, we would hit a certain point and the board would accelerate. With this board here, we got to Signal Hill before the sun had come up, and we needed to take a run. So, on the first run, I went about halfway up the hill and shot down. On the second one, I climbed a little bit further and went down. On the third time, it was just getting light, the contest was that day, and we went up to the top of the hill. I ran, pushed off and hit the bottom of the hill on this board. I remember absolutely hitting the train tracks on two wheels, then on the other two wheels, back and forth and on through the intersection. It was literally a life-changing thing. All of the local guys came out and said, “You guys can’t ride on the hill.” We got to talking, and I asked, “How do you slow down before you go over the tracks?” They said, “We slow down before we hit the tracks.” I said, “There’s something to this. It’s scary, because I’m accelerating at the bottom of the hill, but these guys are slowing down.” Again, it was our equipment. So, Signal Hill played a huge part in my downhill racing experience. Those were some really good times.

I wanted to get a shot of you with the Turner board with the camber.

Okay, this board here is what we called the cut-away. There were basically two styles in slalom racing that came out of all of the years of doing this. This board came a little bit later in time. There was a parallel stance and a surf stance. 90% of the guys skated in a surf stance. But then there were some guys who came along, like Bobby Piercy, a whole slew of guys who had skied and did a lot of slalom. So, Bobby Turner made this board, and you can see the camber in it. It was designed so that when your weight is on the board, it will lie flat, and when you release your weight, the board will flex. So, this board was made so you could skate parallel stance like Bobby Piercy. Mine was a surf stance. The difference in the two stances was pretty clear. Today, they ride more surf style than the parallel, because of the way the equipment has changed.

Back then, Turner made three boards. There was a street skater, which was a longer board, the Bobby Piercy model, and the Tommy Ryan model. These boards were so far ahead of their time. This board has got to be 30 years old, and there is nothing like it. I have a pretty nice collection of boards that are 30 to 40 years old and they look brand new. But, these boards changed the sport of slalom. That’s not to say that the sport hasn’t gone past what we were doing then. Of course, there was a rivalry between G&S and Turner forever. But, their boards were different. Theirs had a flex under the trucks, and ours had a flex over the trucks.

Tommy Ryan and Bobby Piercy. Photo: Chuck Saccio

It’s funny that the G&S boards in the mid ’60s were really stiff like you mentioned and then got really flexy in the ’70s.

Again, they were trying to keep up with the times. Their train of thought was, “Do this and sell it,” and ours was we wanted to do what rode the best. It wasn’t all about money back then for us. I could have stayed with G&S, but I rode what I wanted to ride. Then I got a chance to develop my style of riding and my kinds of boards, which again played a part in the trucks and the wheels. The way skateboarding was changing wasn’t because of what sold more. That just wasn’t where I was at in the sport. To me, the sport was to go out and race on Sundays, and that’s what I wanted to do.

At the same time, we were going to La Costa, we were also skating ditches, reservoirs, and pipes.

Yeah, and that’s where the wood boards came in. I don’t think anyone who skated back then at our level had just one board. We had a quiver of equipment. I remember when John O’Malley opened the first skatepark in Carlsbad, we all looked at him like he was nuts. There were bumps out in the middle of this thing, and bowls. I think it was one of the first skateparks ever made. I just remember thinking, “What is this?” There were literally pyramids out in the middle of the flat. He had a vision and he knew what he was doing. Then, all of a sudden, skateparks started popping up.

But, being street skaters, we went to an elementary school that had this big, grass knoll that went down to the lower level, and a big series of steps. Behind the classroom was a big asphalt wall that ran the whole back length of the school. We thought that was the coolest thing ever because we were surfing this concrete wave. Just the other night, I was looking at some super 8 video from back then with Dennis Schufeldt and all of these guys. It was unbelievable. They were skating down the steps, “Duta-duta-duta-duta!” It just didn’t matter what we rode, we were skating, riding down the grass, making these trails in the grass. We would ride anything. You’d see a ditch off the side of the road, and sure enough, we were in there trying to do something. That’s where the kicktail came in.

Skateboarding has come a long way from when I was a little kid to now. It’s phenomenal how far it’s come. I really like to believe that all of us played a part in the revolution of skateboarding. It would have happened, regardless. But, Tracker, Turner, and G&S will go down in history, because we were there from day one, and that’s why we’re here today, sitting around as family. We’re really blessed we got to spend those days innovating a sport that’s like no other. I don’t know of any other sport that’s like skateboarding. And it’s not just me, everybody played a part in it, and that’s what’s so cool about this, because the brotherhood in skateboarding is phenomenal, how we’ve stayed together for 50 years. A lot of people haven’t made it 50 years, and we’re still cherishing the days we spent together with our tales and our good times, man.

Tommy Ryan on the Tracker Ramp, the first portable halfpipe. Photo: Lance Smith

There are not a lot of people who can say they’ve been here since the roots of the whole thing—especially people like you who were involved on a manufacturing level. Even though you were a team rider, you were close to the source and close to the evolution the whole time.

I’ve been married for 35 years to the same wife. I’m blessed that I’ve had this legacy to leave for my son. Whether I go another step forward or not, the legacy is there—with you guys, with everybody. I’m content if I never go any further. I’m content with what I’ve done—putting my devotion, my energy into the sport. I’ve done my share and gave back to a sport that’s been excellent to me. I really feel blessed to have known you, Lance, and the people who are involved. The Internet has played such a big part in us staying together as a family. It’s cool for people you haven’t talked to in a really long time to wish you a happy birthday. After 40 years of knowing them, you know it’s just a cool thing. I’m sure a lot of other sports are like that, but skateboarding was definitely really good to me.

And you still skateboard today?

My dream is to do it at 60. I don’t know if it will happen, but I would surely love to. My wife’s not too keen about that. I have the urge to still do it. I still street skate. I still have all of my equipment.

Lance Smith: What would it be like to do 60 mph at 60?

I would like to do it on Signal Hill on this board right here. I started speed racing on this board and it still has 60 mph in it, all day long with the right equipment. We used to coast at 50 mph, so 60 mph is nothing that we can’t do. But, we’ll see.

Tommy Ryan and friends. Photo: Lance Smith